As an architect, I tend to look at life through a designer’s lens; my desire to edit, improve, and create is constant and, probably, innate. For the past twenty-five years, I have supplemented my passion for architecture with the practice of Bonsai. It grew from a collision of other interests – gardening, sculpture, and science, but truth be told, I didn’t know anything about Bonsai until I saw the original Karate Kid.

There is a classic scene where Mr. Miyagi tells Daniel-san, “Close eye. Trust. Concentrate. Make a perfect tree down to the last pine needle. Wipe mind clean of everything but – tree. Nothing exists whole world, only – tree. You got it? Open eye. Remember picture? Make like picture.”

That kind of approach can transform all types of design. I see many tethers connecting the art of Bonsai and architecture, in particular.

The first is function. In houses, the program of interior and exterior spaces must support the lifestyle of its residents – it must create a stable shelter and take into account things like access to the outdoors, room configuration, and balancing private spaces with rooms for gathering. In Bonsai, the health of the tree depends on certain horticultural requirements – everything from adequate water and sun, to soil composition, root maintenance, and pest control.

-

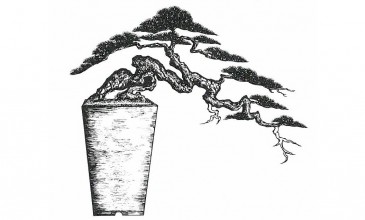

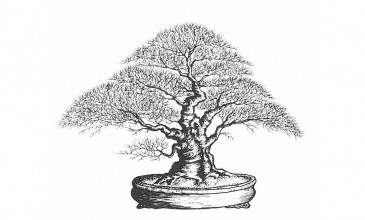

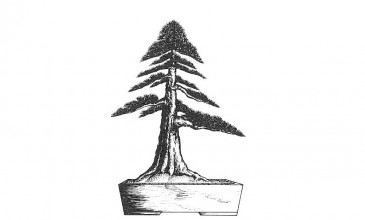

The second is form. Houses have structural idioms that we must design within – roof shapes, symmetry or asymmetrical balance, regulating lines of elevation, and proportional massing, to name a few. Bonsai also has a fundamental language to consider and manipulate. In the wild, apically dominant trees tend to grow in a triangular shape. Roots spread down and out thanks to a phenomenon known as geotropism, while phototropic leaves and vines on the same plant bend up and toward the light. Central stems and trunks naturally taper to support fine branches and foliage.

Certain formal qualities are predetermined. To these, an artist adds creative vision. An architect or horticultural artist navigates the framework, looking to create a unique expression of beauty within the functional requirements of his or her medium.

-

A third (and perhaps the most important) comparison is that of adaptability. A house will evolve over the years, decades, and even generations, as families grow and age or reduce in size. Good design will anticipate some of this change, and easily accommodate additions or subtractions that support new circumstances in the future. Similarly, a Bonsai tree is alive, and therefore always changing. Every season, the tree has a different look. Its branches and foliage must be tended over time. Sometimes, a tree will outgrow its original design and need to be completely re-considered. If a Bonsai tree is not changing, it’s dead.

That’s a funny thing to think about as we embark on some big changes here at the firm. The photo above, taken on a particularly calm morning last summer, shows a 12-year-old trident maple soaking up the sun in the window of my office on Clinton Avenue. Today, as I unpack my new space at 533 Palmer, I can’t help but wonder what new adaptations we will need to make, and how the light in a different space will affect new growth…

About the Author:

Charles e. Orr, AIA, LEED GA, is a Principal at Hutker Architects, and the longest (but not the oldest!) member of the Cape Cod Bonsai Club, which celebrated its 25th year in 2014. He joined in the inaugural year and is currently serving as Vice-President but has held all of the offices at one time or another! To learn more, visit www.capecodbonsai.org